Finding Optimal Values for Various Concurrency Solutions Using K6 Tests

Introduction

To resolve concurrency issues that can occur in a ticketing system,

we explored various solutions and implemented concurrency control methods using the following three approaches:

- Optimistic Lock

- Pessimistic Lock

- Distributed Lock

A widely held belief is that “optimistic locking is advantageous when contention is low.”

But is that really true?

What criteria define “low contention”?

We decided to write test scenarios ourselves to empirically determine which locking strategy is more advantageous under different situations, and to analyze the results.

Main Content

To break down the scenarios, we first identified variables involved in ticketing situations.

Common Factors

The first two common variables we selected were the number of users attempting to ticket and the number of remaining tickets.

Variables by Lock Type

Optimistic Lock

The core of resolving concurrency issues with optimistic locking is for the developer to explicitly handle exceptions arising from version column mismatches.

Typically, this is implemented by requesting retries through exception handling using try-catch blocks.

In our project, we used Spring’s @Retry annotation to handle retries.

@Override

@Retryable(

retryFor = OptimisticLockingFailureException.class,

backoff = @Backoff(delay = 100),

maxAttempts = 10

)

public void assignPurchaseToTicket(UUID ticketingId, UUID purchaseId, int ticketCount) throws ConcurrencyFailureException {}

This code contains two variables:

maxAttempts, which means the maximum number of retries allowed, and backoff, which is the interval between retries.

We added these two values to our set of variables to determine their optimal configuration per scenario.

Pessimistic Lock

For pessimistic locking, there were no additional variables.

Distributed Lock

To implement distributed locking, we used the Redisson library, which supports Pub/Sub mechanisms.

Distributed locking with Redisson notifies subscribed clients when a lock is released.

// CreatePurchaseWithDistributedLockUsecase.java

@Service

public class CreatePurchaseWithDistributedLockUseCase extends CreatePurchaseUseCase {

private final RedissonClient redissonClient;

public CreatePurchaseResultDto createPurchase(CreatePurchaseCommandDto command)

{

var ticketingId = command.getTicketingId();

String lockName = ticketingId.toString();

RLock rLock = redissonClient.getLock(lockName);

long waitTime = 10L;

long leaseTime = 3L;

TimeUnit timeUnit = TimeUnit.SECONDS;

// Wait up to 10 seconds, hold the lock for up to 3 seconds

try {

boolean available = rLock.tryLock(waitTime, leaseTime, timeUnit);

if (!available) {

throw new TicketConcurrencyException();

}

super.createPurchase(command);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new TicketConcurrencyException();

} finally {

rLock.unlock();

}

}

}

We set waitTime, the maximum wait time to acquire the lock, and leaseTime, the maximum time to hold the lock, as variables.

Summary

In summary, there are six variables:

-

Common Factors

- Number of tickets

- Number of users

-

Optimistic Lock

- backoff

- maxAttempts

-

Distributed Lock

- waitTime

- leaseTime

Experiment Method

To find the optimal locking strategy and configuration values per scenario, we conducted tests for each combination.

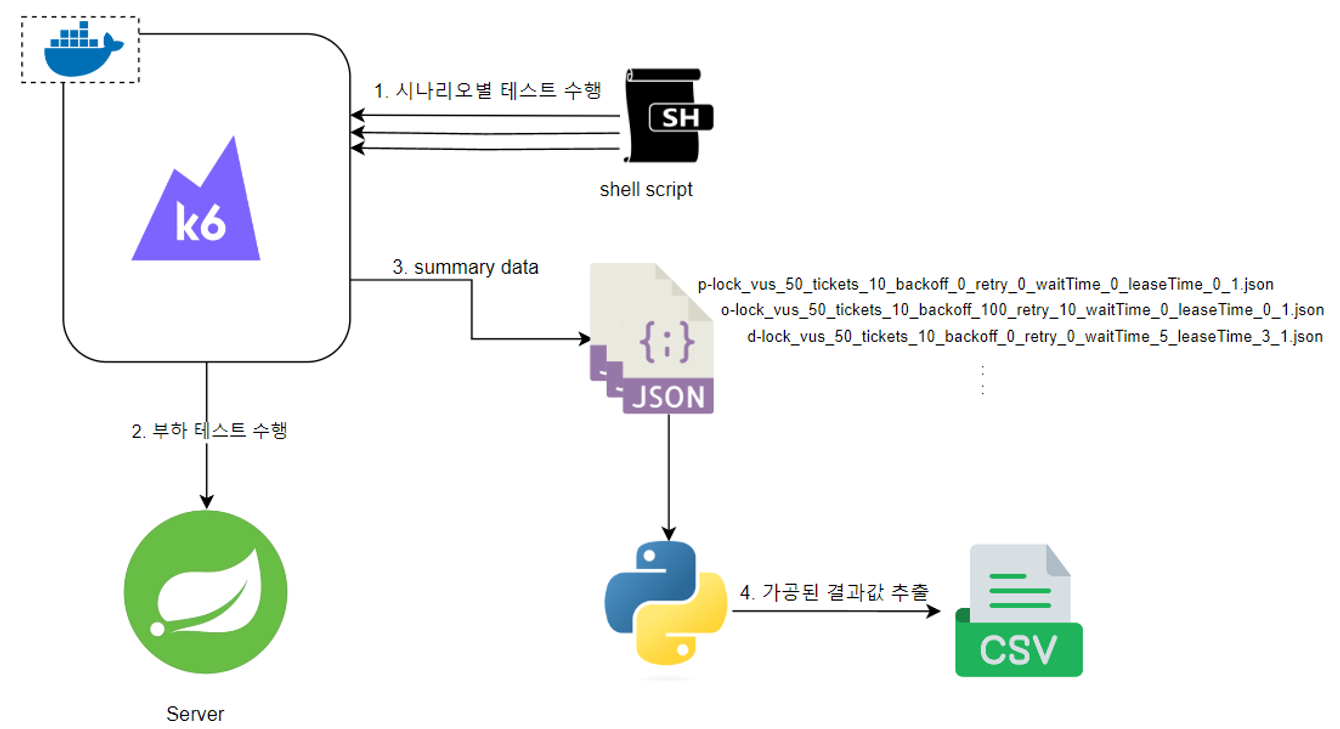

We set three values per variable, configured shell scripts to run K6 load tests for all combinations,

and used Python scripts to collect the results.

A simple diagram of the experiment process:

Initial Value Selection

Due to resource and time constraints, it was impractical to test all possible combinations of values for all variables.

Even testing three values per variable for six variables results in 3^6 = 729 combinations, and assuming each test takes 30 seconds, it would take about 6 hours (..).

Therefore, we decided to limit it to a maximum of 3 values per variable.

Common Parameters

- Number of tickets The number of tickets was set to 10 / 100 / 1000. These were assumed to represent very small, small, and medium scale ticketing loads.

- Number of users The number of users was set to 10 / 30 / 50. This is much smaller than the total expected traffic during real ticketing because we implemented a queue system. Having all applicants compete simultaneously would be both unrealistic and detrimental to performance. We assumed a scenario where a queue sits in front of the entire server, allowing 10 / 30 / 50 users to enter at a time, with concurrency occurring only among them.

Optimistic Lock

-

backoff

In most references that used optimistic locking to resolve concurrency issues, the retry interval (backoff) is set to a fixed value.

We hypothesized that this approach could be improved in performance with random backoff,

so we used an approach where the retry interval is a random value between minBackoff and maxBackoff.

So how should we decide the minimum interval and maximum interval?

For the minimum time, we assumed that any retry attempt made while the original transaction has not yet finished would fail anyway,

so we decided to set it greater than the average transaction execution time.

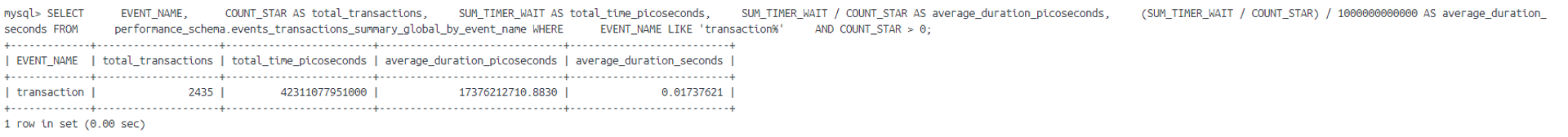

You can find the average transaction time by querying the

transactions_summary_global_by_event_nametable inside MySQL’sperformance_schema.

Using a simple query, we obtained the average execution time in seconds:

SELECT

EVENT_NAME,

COUNT_STAR AS total_transactions,

SUM_TIMER_WAIT AS total_time_picoseconds,

SUM_TIMER_WAIT / COUNT_STAR AS average_duration_picoseconds,

(SUM_TIMER_WAIT / COUNT_STAR) / 1000000000000 AS average_duration_seconds

FROM

performance_schema.events_transactions_summary_global_by_event_name

When testing under various conditions, the observed average transaction duration was about 170ms, so we set minBackoff to 200ms.

For maxBackoff, we thought that if the retry time exceeded 1 second, the remaining time after the transaction ended would be unnecessarily long,

so we arbitrarily set it to 300 / 450 / 600.

- retry For the number of retries, we couldn’t find a clear guideline to reference, so we arbitrarily set the values to 30 / 60 / 90. To ensure consistency, we decided to pick the minimum value that maintained an acceptable success rate.

Distributed Lock

- waitTime One of the variables in distributed locking is waitTime, the maximum wait time to acquire the lock.

- leaseTime leaseTime is the maximum time a lock can be held.

The reasoning behind the initial values for waitTime and leaseTime was as follows:

- If waitTime is significantly shorter than leaseTime, failure rates would likely increase.

- Therefore, we decided to maintain some linear proportion between them and select the minimum value that maintained an acceptable success rate.

The final initial values:

- leaseTime: 3 / 5 / 7

- waitTime: 5 / 10 / 15

Conclusion

Execution Results

You can find the full execution results in the attached file.

Analysis

💡 conflict_rate = tickets / vus (degree of contention)

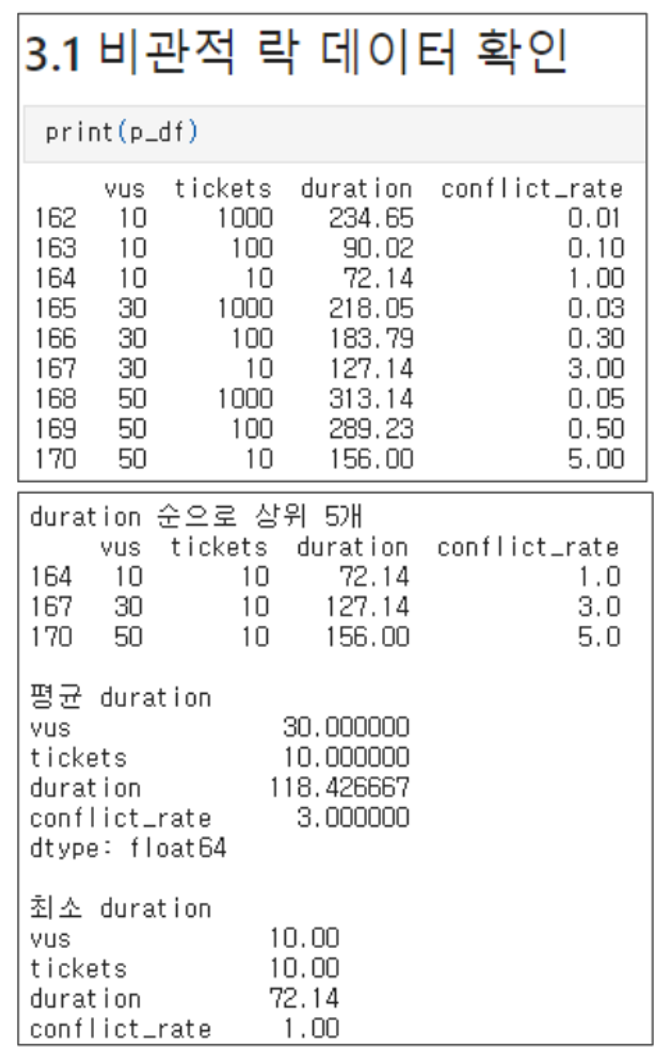

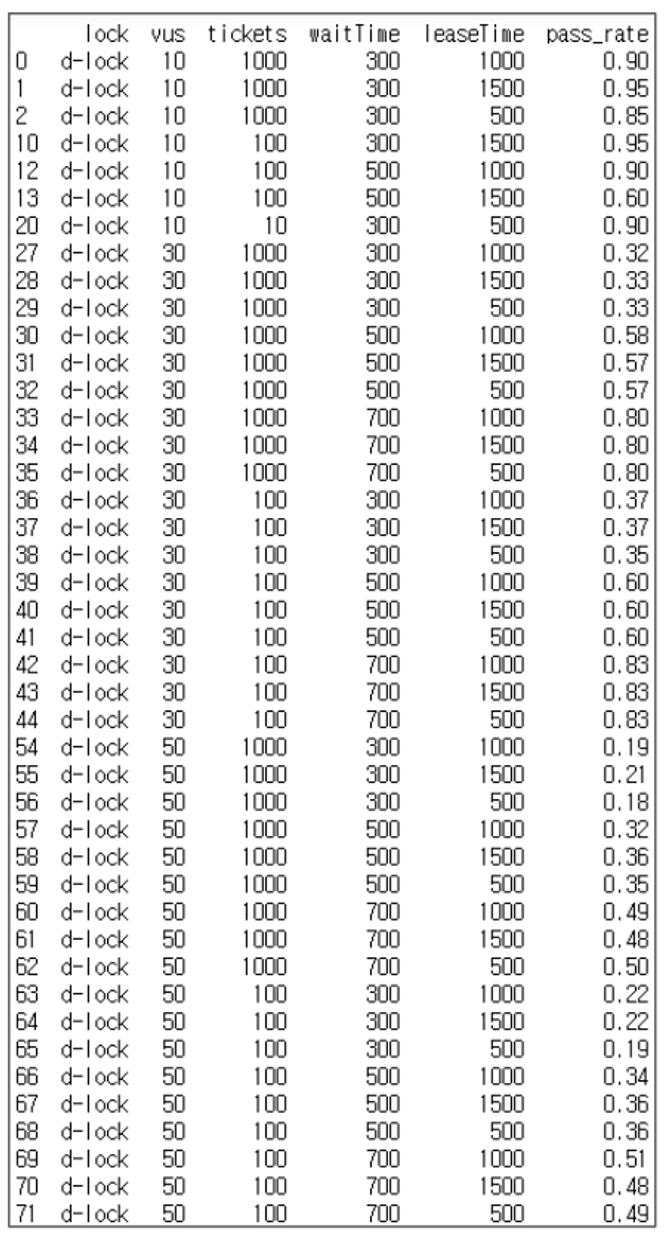

Pessimistic Lock

Results for pessimistic locking.

Although there were no special variables, we confirmed that as contention increased (number of users relative to tickets), duration also increased.

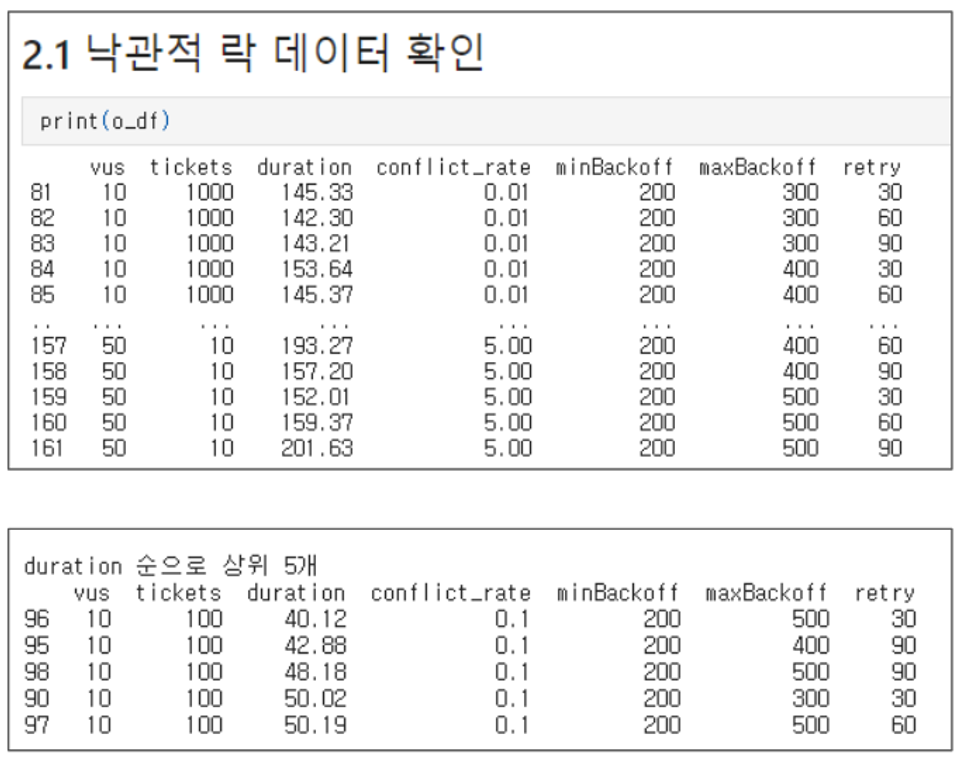

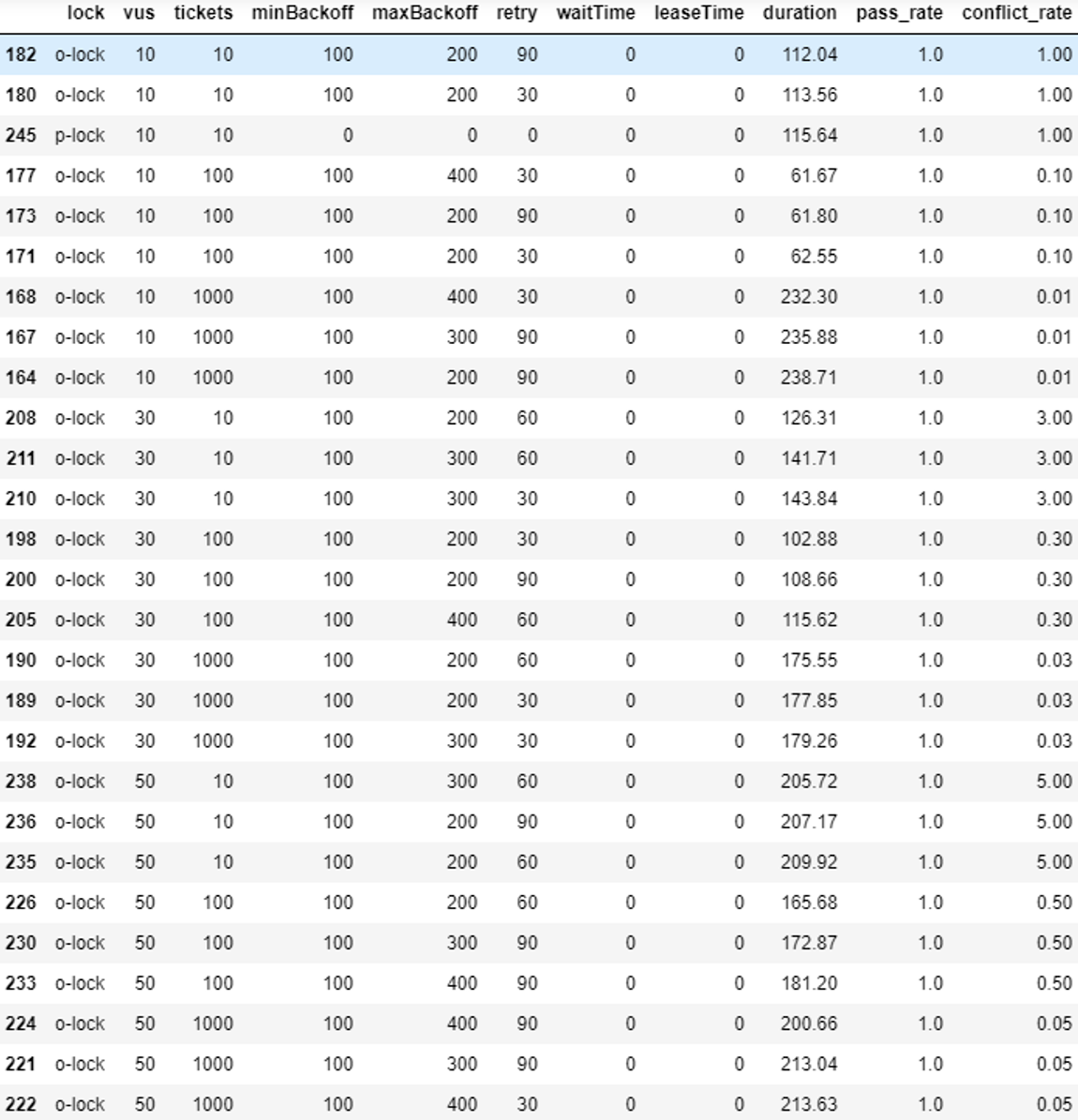

Optimistic Lock

Results for optimistic locking.

From the second figure, we drew the following conclusions:

-

Beyond a certain threshold, the retry value does not affect duration

- However, in high contention scenarios, too low a retry count will impact success rates.

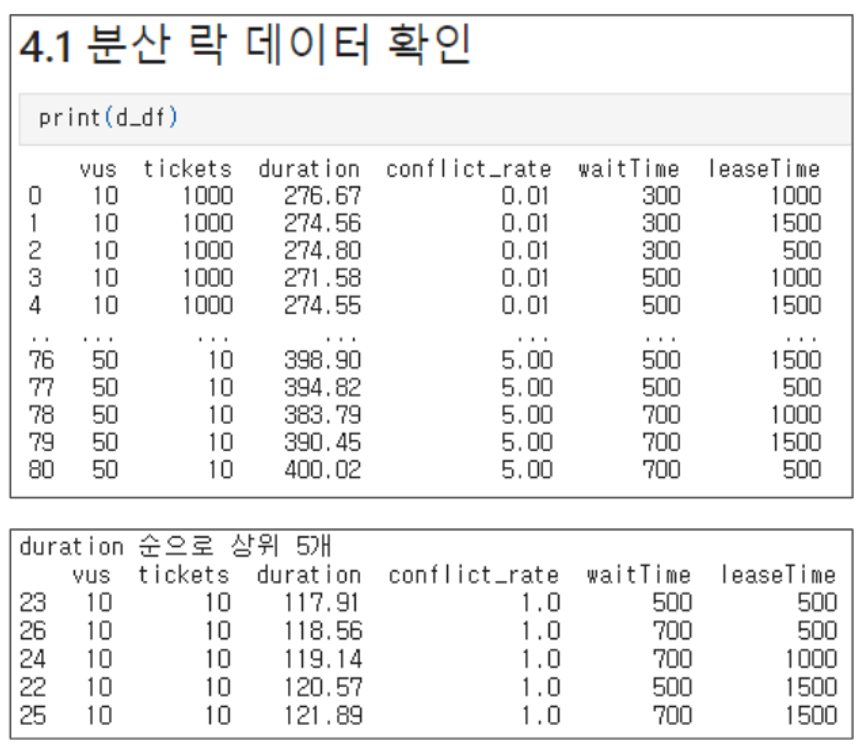

Distributed Lock

Overall, distributed locks showed a tendency for duration to increase proportionally with waitTime and contention.

Additionally, the overall duration was higher than 100ms, exceeding the durations observed in optimistic and pessimistic locking.

There is one more indicator to consider in distributed locking:

Success rate, meaning the ratio of total requests to the lower of VUS count or ticket count.

We observed two characteristics in the results:

- As contention increases, success rates decrease This is somewhat obvious.

- Under the same conditions, higher waitTime leads to higher success rates Since tryLock returns failure when waitTime is exhausted, this is also clear. However, under the same conditions, leaseTime had little impact.

-

Increasing waitTime increases success rates but also increases duration

- This shows a trade-off.

Summary:

Overall statistical results for all data.

In most cases, optimistic locking showed superior performance.

Even in cases grouped by VUS and ticket count, optimistic locking was the fastest.

Conclusion

Let’s summarize the experimental findings:

-

Under low contention conditions, optimistic locking is advantageous

- This supports our initial assumption.

-

Distributed locking performed worse compared to optimistic and pessimistic locking.

- It showed poorer success rates and duration, which are the most important metrics in a ticketing system that must guarantee consistency.

- To increase success rates, you must increase waitTime, which in turn increases duration.

So is distributed locking useless?

Does that mean distributed locking is useless?

Not at all.

In scenarios with high contention or where multiple servers must be synchronized,

or where task execution itself takes longer, distributed locking can be more advantageous.

As always,

consider the trade-offs carefully, select the appropriate locking strategy, and tune the values to fit your environment.

Appendix

You can find more detailed data analysis on team member Chaeyoon Lim’s personal blog:

댓글남기기